Methods for

Social Studies

How

Do I Keep My Ideals and Still Teach?

PAGE 2

Interest and Integrity

First, get their attention, and develop a why to learn. Then,

keep

your promises, be what you say you are. You may remember the Seuss

story,

the "Sneetches," about Sylvester McBean, the scamster who sold star- on

and star-off patches to the Sneetches. If you do not remember the

story,

drop this and go read it. McBean was good at getting the Sneetches

attention,

and selling them a why to behave, but he was a dirtball, had

no

integrity, and finally the Sneetches figured him out. Kids are probably

quicker than Sneetches in discovering whether or not you are authentic.

They will test you until they decide they love you. Then they will

forgive

you.

This is not a solely student-centered approach. This approach

recognizes

the intersection of student abilities and interests with the

educators’,

and with the resources of the community where they reside.

It's About Time!

Time is a precious commodity in school, and someone else is always

trying

to steal yours. It is a social studies method to try to expand your

available

time-for yourself and for your individual kids. This means fighting for

lower class size, against more bureaucratic paperwork, for aides and

parental

involvement to assist in the classroom. It also means fighting to have

more time to reflect on what you're doing during the working day, and

more

time to pursue your own intellectual interests outside your teaching

situation.

That might include struggling for free university tuition, paid

sabbatical

leaves every five years, a shorter working day, longer vacations, and

so

on.

Inside the school, time is also a critical issue. How will the

kids'

time be consumed? How much free time will they have, considering that

there

is a direct link between freedom and discipline? How much time will you

waste if you are not given a phone, a bathroom, a laboratory, and a

computer/library

available at all times to every kid in the class? Resolutions to all of

that is a social studies method.

I Search Papers (also from Ken

Macrorie)

Here is a link that over-explains Macrorie's idea that you start with

something

the student is interested in, and have the student research it. http://www.edc.org/FSC/MIH/i-search.html

The History Wars

Historians are deeply divided. Some of them see history as a product of

great men (sic). Some historians see history as a struggle to reach

God,

the divine, and they will do a good deal of work trying to determine

what

God is telling them. Others see history as a struggle for consensus,

especially

in the US. That means that all of history is a high-point of the

creation

of general agreement. These people would focus on consensus builders,

Lyndon

Johnson before his presidency for example Others see history as the

history

of class struggle. These historians will focus on the working classes

and

their representatives, often communists. E.P. Thompson and W.E.B.

Dubois

were leaders in this school of history.

Kids can understand this. They can take up a school of history

as their

own and struggle for its outlook in discussions and debates about how

things

work, which always lead to questions about what is next-and what to do.

All of history is an interpretation of the past, through a standpoint

in

the present, that is imbedded with a call for action in the future.

Class Council

Set up an internal class council to decide things that are important

-and

things that are not. "What shall we choose to learn? How shall we go

about

learning this? Who shall be in charge of distributing papers today? How

shall we resolve disputes? What shall we take from our class to present

to the rest of the school?"

Room Title

Other teachers love this, and so do some kids. If you do, do it. I

don't.

Have the kids decide the name of your classroom. I have seen everything

from BattleBotKids to Utopia. What influence does a name have over what

a thing, or a person, is?

Dub the Room

Other teachers love this, and so do some kids. If you do, do it. I

don’t.

Have the kids decide the name of your classroom. I have seen everything

from BattleBotKids to Utopia. What influence does a name have over what

a thing, or a person, is? Too often, I see rooms named the Deadly

Mantis

Hurricanes, and too infrequently, The Dancing Cuckoos.

Power Symbol to the Speaker

This is a nice move when discussion is good and passions are high.

Simply

create a power symbol (probably something that is not threatening, not

stick) that is the sign that the holder is the speaker, and the only

speaker.

The speaker, at the close of the comment, passes the symbol to someone

else.

Undoing the Fear of Freedom

Even after a few months of kindergarten, many children have learned to

be unfree, to fear freedom, to oppose the risks PF exploration and a

struggle

for meaning. Your task is therefore often at least two-fold, to undo

this

fear, and to point the way toward a more free way of doing things. How

do we spot the fear of freedom? In little kids, we see children who are

afraid to write because they have been taught that the only good

writing

is writing that is spelled correctly: a little first grade girl who

will

not write the word, “music,” which she wants to write about, and

instead

writes, “zoo,” because she knows how to spell it. In college students,

we often hear, “Just tell me what to do and I will do it.” Both

students

are quite sure they are doing the right thing because this is what they

have been taught. It’s a slave mentality, a consciousness that is

constructed,

entirely, from the outside, usually from dominance, elites.

With standardized curricula and tests, this fear is ratcheted

up with

external rewards and punishment. In Michigan, for example, the state

test,

the MEAP, is administered by the Treasury Department, and rewards are

offered

to kids who take it, financial punishment meted out to schools with low

participation. The Detroit Free Press suggests that the way to prepare

for the tests is to play “How to Become a Millionaire” with the kids. http://freep.com/news/education/meap20_20010120.htm

So, with the double problem, the fear of freedom, and

the kids

belief that this fear is really academic rigor, there is a good deal to

be undone. Much of this little book is about how to do that. However,

one

pattern is clearly useful: to engage a particular subject that is

routinely

ignored, or falsified, a subject that has some interest to the kids,

and

take it apart. In my experience, this can begin nearly anywhere but the

ignorance that is promoted about Vietnam, (http://www.richgibson.com/HoChiMinh.htm)

fascism, (http://www.richgibson.com/teachingholocaust.htm)

and methods of analysis

(http://www.richgibson.com/scedialectical4.htm)

have proved out well. In earlier grades, trickster

tales (described below) are a nice place to begin.

Beyond subject area entry points, it is key to maintain

freedom of expression

in the classroom, meaning the freedom to say nearly anything that does

not demonstrate contempt for the people in the room, and to say that

anything

without fear of retribution (grades, etc.) In the absence of this

freedom,

and the trust it produces, the others all fall apart. They will not

tell

you they are not free unless they feel free to say it. If you don’t

know

about it, how will you deal with it? Your task is to change people, not

to let your ego become so fragile that you cannot allow the routes ino

their minds be exposed. Specifically, it is one thing to allow a

theoretical discussion about racism in a classroom to progress to the

point

where some students are expressing clearly racist views. It is another

thing to allow those racist views to be directed to people in the room,

to be used to destroy their freedom. You must know who in you class

hold

fearful (racist) ideas, yet you must not allow those ideas to go into

effect.

Teaching is not for the faint-hearted.

The Mute Flute

A Detroit teacher whipped this out when I visited her class, which was

slowly dissolving into a heated but unproductive debate as everyone

joined

in. Rather than switch off the lights, or clap a Bo Diddley beat to

which

kids are expected to respond with a quick clap-clap, she mimed a silent

flute, and as she moved around the room, not playing it but miming its

sounds, the kids joined in, until the silence allowed more organized

debates.

Political Cartoons

First bring some cartoons to class. Then let the kids make their own.

Some

of these become really delightful. A cartoon does not have to be just

one

page, but can become an entire book. See, for example the cartoon books

of the "For Beginners," series, like "Marx for Beginners." Or, "The

Incredible

Rocky." Cartoons can be silent graphics too. See the IWW poster on my

www

page. For examples of terrific work by kids, see the Zino Press

book, Editorial

Cartoons by Kids 1999. http://www.zinopress.com

Heroes Schmeroes Sez Me

Have your class make a list of heroes (or two lists; one of the most

important

people, the other of the most famous.) Then take count of how many men,

how many women, how many people of color, how many people of the

working

class. Consider how quickly a hero can be wiped out, like Paul Robeson,

one of the most famous people in the world in the 1940's. Or consider

Joe

Stalin and Fidel Castro, both once Time men of the Year. Consider the

chances

of becoming a hero on the landscape today, if you are born on a small

Carribean

island for example, or in west Africa. Would a person who worked in a

iron

foundry for thirty years, to put children through school, be a hero?

Then

unpack what values we use to decide who a hero is. Are these values

that

serve most people, or values imposed by dominance to prop up unjust

rule?

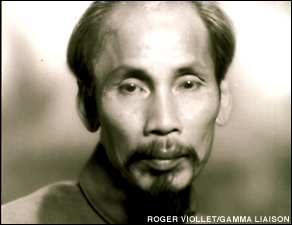

Why do we think we need heros? Is John Brown heroic? Ho Chi Minh? For

me,

the search for heroes is not terribly enlightening. I believe that what

is heroic is the processes of knowledge that billions of people have

sacrificed

to discover over centuries. The notion of heroes, to me, suggests that

some people are simply vastly better than the rest of us-and then we

are

appalled when we find out they are not: Jefferson raping his slave for

example. Moreover, creating heroes usually obliterates people who are

not

in the immediate gaze of the powerful.

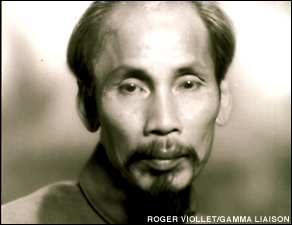

Ho Chi Minh |

|

Photo or Video Essays

There are many kinds of literacies. Some kids who do not read or write

well can be engaged by the possibilities of video/photo essays, which

require

the same skills. A video map of the geography of the playground

described

below might be very interesting.

The Art (Music, Dance, Film, etc.)

Detective

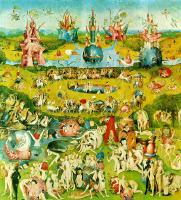

This is fun. Grab a piece of art, say, something by Hieronymous

Bosch, like the Garden of Earthly Delight (click

on image

for larger view). Have the kids investigate the work in

detective

fashion. What society would have created this? What would work be like

in this society? What about literature? What era does this fit into?

Why?

What are the clues that you are using as evidence? What kind of

medication

would be prescribed for Bosch today?

Art is never separate from its social context, although some

artists

do seem to be able to vault forward in time, signaling what is to come,

often in foreboding terms. See the passage in Bosch above.

Grow Stuff and Eat It

Lifetime radical Grace Boggs of Detroit has been instrumental in

creating

a project called Detroit Summer, an effort to unite education workers

with

students, community people, parents, grand-parents, nursing home

captives–the

entire community, in a struggle to not simply collectively grow gardens

in the midst of urban collapse, but to create the educational community

that grows along with the vegetables. Detroit summer addresses a myriad

of social problems, positively, by investigating the sciences of city

farming,

and uniting a community that has been divided by age, race,

ability/disability.

The gardening brings together theory and practice, nature and labor,

and

people who have been segmented, to their own detriment. For example,

seniors

in the community meet and lead youth, who the seniors often feared.

Youth

learn to take the space in their communities, and use it creatively.

And

everyone shares the produce, thus meeting the old teachers maxim: when

in doubt–feed em. http://www.detroitsummer.org/

Mrs Sutfin’s Immortal Class

In a state that can go unnamed, one Henrietta Sutfin came to teach a

second-grade

class in early November. The 43 kids had already gone through three

teachers,

each of them a burnout. The last I had heard, the kids were refusing to

read and no one had time to go see if they could. I came to know Mrs

Sutfin

early in her career, when she was well over fifty. She was a grandmom,

returned to teaching after raising more kids than I can remember. I was

her grievance representative. She never lost.

Mrs Sutfin greeted her small mob on her first day with a sense

of cheer,

joy, and firmness that comes with having dealt with dozens of great

child

tragedies and curiosities, and challenges. She took pictures of the

kids

and when I came to her classroom, she had a poster of the children in

several

poses. The two I remember, “We can be silly!,” with the children’s

faces

contorted in an endless variety of parental horrors, and, “We can be

serious,”

with every child peering steadily into a book.

I was visiting Mrs Sutfin that day just to say “Hi,” to a new

colleague.

As I walked down the hall toward her room, another teacher began to

pass

me by, going in the other direction, trailed by her classroom of

probably

35 fourth graders, all in a neat line, each just more than an arm’s

length

behind the next, all with both hands clasped behind their heads. She

led

the line, then stepped aside as the group was about to pass me, and

whispered

proudly, “Takes a month to get ‘em like this!” As she turned toward me,

away from the kids, one little girl, the third in the line, burst out

of

position and began to dance, not march, down the hall. Every other

child

remained in line, hands behind heads. By the time the teacher turned

back

to her minions, the little girl was back in line, uncaught.

Mrs Sutfin was reprimanded later in the day–for allowing her

class to

go to lunch without forming a good line, without being sure that the

children

could not touch each other. She called me and I stopped back the

following

day, just around lunchtime.

Mrs Sutfin’s kids were marching, well, high-stepping, down the

hall,

in near-perfect line, each child with the fingers on each hand clasping

one of their own ears, and pulling. Every kid had a tongue out, and

every

kid was in full glory of making their most ever-so-wicked face. In a

day,

Mrs Sutfin’s gang became a class. No one ever tried to discipline her

again.

They started to read.

Antennas Up! The Author's Chair

Henry Miller, not a kids' author, was once asked how he wrote. "I just

put up my antenna and I write what comes through." Many writers talk

about

similar experiences. Every kid is an author. Every kid is an audience.

Ann Henry, a longtime Detroit educator, put that all together and came

up with an Author's Chair, one higher than all the rest, from which the

child writers could declaim. She told her fifth graders Miller's story,

but as I remember it she changed his name. When it came time for a

reading,

the shout went, "Antennas up!" Then quiet settled in as the author

proudly

set out on her writing, in full voice.

Enablers

Ken Macrorie, in his book Twenty Teachers, lists 45 characteristics of

people, enablers, who teach well (p.231). Here I will paraphrase

XXX that stood out for me. Enablers....

1. Get people doing good work that counts for them

and the

people they care about.

2. Work along with the learners, and make their work public.

3. Aim high.

4. Don’t tediously lecture or give conventional tests, but set up

dialogues

that link experience and theory, practice and research, understanding

that

learning can build on failures as well as success.

5. Build on imaginative work through storytelling.

6. Urge people to become creators of their own research, responsibly,

so the become finders as well as receivers in seeing the connections,

the

relationships, of (for example) emotion and reason, the particular and

the general, playfulness and planning, the individual and the

group.

7. Are never cruel, yet rarely praise excessively, while they offer

time to complete the work through polishing, reflection, and

reexamination.

8. Link classroom practice with the world outside.

9. Create communities where peers can profit from and build on the

work of peers, using grades, if at all, in ways that least interfere

with

the intrinsic desire to learn.

10. Never deny learners their lives, and let them go when the time

has come.

I have always found the kindness that forms the skeleton of Macrorie’s

work to be valuable. I hope you will find time to review his

books.

The Real Map and Standpoint

What should a map really look like. There are several maps which seek

to

reestablish how we see the world, some by demonstrating the true size

of

nations, others showing the topography without boundaries, others

showing

the entire world in a triptych. Have the kids make a map, but suggest

that

their view point is a small island in the southern hemisphere. Which

way

will be up?

Newspapers or Newscasts about an

Area of

Study

My favorite of this is a "Coal Miners Journal" done by a teacher in the

Copper Country in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. The kid-written

paper

reported on every imaginable aspect of life there in the 1890's. Women

wrote their stories, men wrote of the mines and their work.

Beginning Wherever and Webbing

All things are interrelated, including all historical events. It really

doesn't matter where you begin, so you may as well begin at the point

of

the student's interest, your interest, or the interest you create in

the

students. For example, you could start a history web with the Tyson

Bites

the Ear Fight in 1997. All of history came to that point and met

itself.

The fighters, two young black men, earning millions in exchange for a

punchy

future, squared off in a ring. On the floor of the ring is written,

"Gold."

The audience is truly multi-cultural, as the rich are these days. On

one

arm, Tyson has a tattoo of Mao. On the other arm, Arthur Ashe. Tyson

claims

to be a Muslim. His opponent is a devoted Christian. The ring referee

is

a real Nevada judge, who now has his own TV show. The state is

represented

in the ring by white sheriffs who invade the ring after Tyson is

disqualified.

Tyson, already a convicted felon, hits a cop, but nothing happens. Ah,

the power of money. An auto worker who did much less than that in

October

2000 in Detroit, is dead, shot by the Detroit Police when he did

not hear them order him to drop a rake he was using to clean his yard.

He was deaf. An auto worker who did much less than that in

October

2000 in Detroit, is dead. The sole representation of a woman in the

ring

is a bathing suited round-number carrier who, in the midst of a near

riot

in the ring as the fight ends, walks through the crowd with her number

held high-and the crowd parts like the Red Sea. A web into all of

history

could start with the video of this fight, or any other moment that

captures

your attention.

Webbing is easy. Start with a central issue that offers

interest and

motivation. This can be drawn with a central circle with many spokes.

Then

allow students to pick related subjects which may reveal something new

or interesting about the initial issue. In the Tyson fight case for

example,

someone might do a biography of Arthur Ashe. Someone else might do Mao,

etc. Arrange for regular research reports so students can keep their

eyes

on the commonality of knowledge as it develops.

Quicky Theater

Tell the kids that they are going to do a quicky (guerrilla) theater

presentation.

They have three to five minutes to get a few key points across. Say

they

want to go to a shopping center to urge people to boycott smoking, but

they know the center will remove them very quickly. They need to

discover

a way to get attention fast, to make their point graphic, to use their

bodies to get the point across, etc. See the book on the IWW, "Rebel

Voices,

an Anthology," for some good examples. Skip Chilcoate has also done

important

work on this. See the indexes of the magazine, "Social Education, "

linked

to the National Council of the Social Studies on my www page. http://www.richgibson.com/other.htm.

Dialectical Scientific Evidence

Social studies research is partisan. Some authors will insist the will

of God is the determining force in social movements. Hence, faith is

good

evidence for them. Others say that things change in precise, lock step

fashion, one piece of history leading to the next, in mechanized

fashion.

Still others say that nothing really changes. For me, history is a

spiral,

perhaps crossing back over itself from time to time, but never

reproducing

anything quite the way it was before. Things do change, but change is

complex.

You need to know where you stand on this debate. Here is a little chart

that may help: http://www.richgibson.com/scedialectical4.htm

Play APBA, Make History

APBA is not an acronym. It is the sole name of a statistically accurate

baseball game. It uses data from real ballclubs throughout history,

real

players, etc. It can be played with dice, or online-at a price. Old

games

like this are all over garage sales, not hard to find. Sports are a

good

way into the social studies. Consider the Black Sox scandals as a study

of injustice. Kennesaw Mountain Landis, once the commissioner of

baseball,

was deeply involved in politics and, as a judge, oversaw the first

major

anti-trust suit against Rockefeller's Standard Oil (Rockefeller was so

boring, Landis could not pay attention). Jim Bouton's, "Ball Four,"

nearly

inverted the baseball world. Ty Cobb was a despicable racist. Sadaharu

Oh may have been Japan's greatest players and wrote one of the greatest

books on the game. Here is a link to an unsung hero, Curt Flood: http://afgen.com/curt_flood.html.

Satchel Paige kept the faith alive despite incredible oppression. Hank

Greenburg was a great player, and a great man. Keeping data on an APBA

season may be the only way you will find to involve some kids in

recording

history. Why not? One good way in: the book, "Baseball Saved Us." You

can

look it up.

Taking it Personally

Have kids write about a historical event from the eyes of a person, who

they choose, who is there; a diary from a southern soldier about to go

on Picket's Charge at Gettysburg for example. This is what I see in

front

of me. This is what I feel. This is why I am here and am about to go do

what I must do. This is what I am holding, wearing, etc. This is my

fear,

and my quandary.

Mentoring the Mentors

Link with another teacher, or do multi-grade work, in which older kids

buddy through the year with younger kids, or kids who have other

skills.

The internet expands this possibility, sharing books, ideas, etc. It

takes

not long at all for kids to learn that one good way to deepen knowledge

is to teach.

Move from the Cover to the Book

Social studies is not a collection of facts or events, but a process of

research that involves many different disciplines, each of which sheds

varying kinds of light on similar events. Research in the social

studies,

and in science, is an effort to move from appearance to essence, from

superficial

understandings to deeper knowledge. Most of that movement is produced

by

an interaction of theory and practice, rebounding back on and

recreating

one another. In many US classrooms, the focus is on appearance. The

devotion

to superficiality is caused, partly, by a factory model of schooling

which

resists work in depth, concentrates on quantity rather than quality.

Let us take the study of flags for example. In many

classrooms, flags

are used unquestioningly, addressed as facts, not problems; fixed

objects

with no contentious history, not multi-dimensional symbols that mean

very

different things to different people. Take the US flag. Early

elementary

kids chant at it, hands placed for some reason on their hearts, or, in

the case of the Scouts (a problem too), in full salute. Many little

kids

have no idea what they are hooting, as Matt Grogan has humorously shown

in his wonderful cartoon book, School is Hell. "I pled a

jean-size

to the flag of de Un-seated fates of Demonica..." In other classrooms

(a

phenomena growing thankfully more rare) kids memorize flags and stick

little

pipe-cleaner flag symbols into world maps.

Consider otherwise. Here is the US flag. Now, part of this

class will

be young black men about to be drafted to go to Vietnam in 1966. Here

is

what Muhammad Ali said you should do. Another part of this class will

be

a Vietnamese woman, in Hanoi, in the same era. Another group will be

Richard

Nixon, planning a comeback, and yet another can be Henry Kissinger.

Will

they all be seeing the same flag? Now, ask the students to look up the

flag of the National Liberation Front.

The move from appearance to essence recognizes that book

covers, appearances,

are important, but insists that there is more inside to be seen and

known.

This interplay is also rooted in the idea that you will be sufficiently

open, humble, to change you mind if your theory and practice

contradict

one another.

The History of Me-and Grandma

The best video I have seen, bar none, is an eight year old girl

interviewing

her grandmother about her trip from Germany to the US in 1939. Why did

you leave Grandma? What does that word mean? Was it hard for you to

leave

your friends? Could you bring your favorite things with you? How did

you

go? I have a map; can you show me? As Linda Levstik shows in great

detail

in her fine book, Doing History, family interviews like this

show

kids their spot in the historical frame, and demonstrate that everyone

makes history. The videos, if your community has the resources for

them,

become priceless family treasures-not a bad move for a teacher. Be

aware

that there will be kids who cannot do this. Grandma may have been a

Nazi,

Dad may be dealing amphetamines. So, offer alternatives. Interview

someone,

maybe a family person, but someone. The bus driver may be just as

interesting.

Hunter Scott and the Sinking of the

Indianapolis

Study deep. That’s the ticket. Here’s a story. Hunter Scott was a sixth

grade kid living in Pensacola, Florida. In 1985 he watched the

film,

“Jaws,” with his father. In the movie, you may remember, the grizzled

shark-killer

captain reminisces about his experience on the battleship Indianapolis

in WWII in early 1945. The captain describes the sinking of his ship

and

four days of terror in the waters as survivors, under persistent shark

attack, struggled to stay afloat. Hundreds of men died.

Scott, having been assigned a history project, asked his

father if the

story was true. His father said he thought it was. So Scott placed a

small

ad in a local Navy paper, seeking to interview survivors of the

Indianapolis

tragedy.

He got one response from a survivor who not only described the

horror,

but who told Scot that the captain of the ship had been unjustly

court-martialed

for the tragedy. The allegation of the court martial, the only one of

its

kind after the war, included testimony from the captain of the Japanese

sub, who reported that the Indianapolis had not been zig-zagging. The

captain

was blamed for everything.

Then began Scot’s pursuit of the truth. After several months

of work,

Scot reached many other survivors who all told the same story. In time,

Scot learned that the captain had been scape-goated by a sizeable group

of admirals and commodores. They had not directed a zig-zag course and,

more, they were trying to protect the fact that Allied Forces had

broken

the Japanese codes. In fact, moreover, the captain had been

zig-zagging,

but as dense darkness fell, he chose to order a straight course,

suggesting

to the men on watch that they return to a jagged course when it became

light. Around midnight, clouds suddenly cleared and the watchmen on the

submarines spotted the Indianapolis and sunk it–in twelve

minutes.

But Scot found there was a deeper story still. The Indy had

been delivering

parts to the atomic bomb. When the ship was sunk, perhaps in order to

maintain

secrecy, the naval bosses knowingly turned their backs, as if the ship

did not exist, and sent no rescue. The only reason the survivors were

found

was by sheer chance, a passing reconnaissance plane. 900 men were alive

when the ship went down. Only around 300 were picked up.

The captain, wrongly convicted, was deluged with blaming

letters from

survivors’ families. He committed suicide, leaving a note, “I should

have

gone down with the ship.”

Scot pursued his action-research over years. Eventually he was

able

to gain congressional hearings which exonerated the captain. Scot was

made

an honorary survivor. Study deep. What you do counts

Here is a good link: http://www.ussindianapolis.org/main.htm

Surveys

This combines math, research, language arts, all of the social studies,

and surveys are sometimes very interesting. The National Student

Research

Center, online, has a great deal of material about this.

Nazi Hunters

Simon Wiesenthal, a Holocaust survivor, made his reputation tracking

down

Nazi war criminals, among them Adolph Eichman. Wiesenthal was initially

marganalized, seen as a crank, as were many people like him who sought

to expose the war criminals in their midst. Wiesenthal later built a

fine

reputation, based on solid action-research. He now hosts the Simon

Wiesenthal

Museum of Tolerance near Los Angeles. Thousands of Nazi war criminals

entered

the US and the West after World War 2 (see "Blowback" by Christopher

Simpson).

Some of them were caught and deported by the US Office of Special

Investigations.

Others were not.

Tracking them can be interesting. Werner Von Braun, the leader

of the

US space program was one of them. Long dead, his history is worth a

critique.

So is the history of the fascist Romanian, Valerian Trifa, deported for

being a fascist, after living for years as a bishop of the Romanian

Orthodox

Church. Even today, his followers are trying to wipe his slate clean.

See: http://www.roea.org/9701/ho00003.html

The former head of the United Nations, Kurt Waldheim, was a

wanted Nazi

war criminal. Interpol, the international police organization, was

founded

by old Nazi’s.

A young girl in Germany, in the late 1980's, decided to make

her high

school project a research into what her villagers had done during WW2.

She believed their stories, that they had done nothing to help the

Nazis,

and that fascism was imposed on them from above. Her teacher urged her

forward. The town's people called her, soon, "The Nasty Girl." A film

was

made about her travails. Now she lives in the US, driven out of her

homeland.

Similar work has been done in the US. For example, in Royal Oak,

Michigan,

a Catholic Church called the Shrine of the Little Flower, a towering

edifice

of the crucifixion, was built with money donated to the immensely

popular,

but fascist, Radio Priest, Father Charles Coughlin. "What did you do in

the war, Daddy?" is sometimes a dangerous question.

Similar questions can apply to the US Civil Rights movement.

“What did

your hometown newspaper have to say about Rosa Parks the day after she

sparked the bus boycott?” or the US invasion of Vietnam, “What did your

paper say about bombing Hanoi, or Cambodia, or the Pentagon papers?”

Of course, one has to know who and what to look for, and to

move judiciously

to avoid a witch hunt, but such is history.

Paper Dolls to Theaters

Kids create paper dolls, or entire theater sets, to reflect the lives

of

characters of the times they study. Consider that they might do not

only

the fashion setters, but working people too.

Visit the VA Hospital

One way to contribute to the community, to demonstrate to students the

results of war, and to start up what can be lifetime friendships is to

take a class to the VA hospital nearby. There usually is one. The vets

are usually pleased to meet visitors who come with appointments, and

who

have a plan. As with any out-of-school activity, this takes

preparation.

What kinds of questions would your students want to ask? How will you

defeat

voyeurism? Can some lasting connections be made? How are the vets being

treated? Would you want to make this kind of sacrifice?

Power and Geography in the Classroom

Until you have made a deal with the custodian, it is a good bet that

every

day you come to teach the chairs in your room will be in neat rows.

Everyday

you will need to think about the power of the institution in all of its

normalcy, and wonder if you want to continue to swim upstream. Every

day

you and your kids should answer: Yes. It is not the swimming that is so

hard. That just proves you are all alive. It is the remembering to swim

that is hard, remembering that your vision is different.

Sitting in groups, where all can look at all, sets up power

relationships

that are at odds with traditional transmission teaching methods (I

know,

you don't, listen to me, read the textbook, because it is on the test).

A collective geography demonstrates in concrete ways that power in your

room is shared, not necessarily equally, but more democratically. It

allows

people to use their bodies to move around, to enter areas of the room

that

might offer space for class plays or a map area or a quiet reading

area.

Rather than a factory, where workers' knowledge is always under attack,

the critical classroom is set up to test ideas in theory and

practice-as

individuals and as a group.

What Goes on Inside Your Brain?

Ask the kids if they have ever had a two sided conversation in their

minds.

"Well, if I do this, this will happen. But if you do, then other things

will happen too." Most kids have. Ask them to write the inner dialogue

of someone they are studying.

The Lewis and Carol Journal

Hey, wait! That was Clark, not Carol! Yes, but what if it was Carol,

instead?

What if women went along? Speculative retakes on history can always be

interesting. What if Hitler had not perseverated at Stalingrad? What if

Washington decided to be King, or if Custer had had the sense to get

lost

before the Little Big Horn, and run for president, or if the Communist

Party USA had decided not to build the CIO? More interesting to me is

to

look in history to discover how Sacajawea has been treated over time.

Each

to his own. Flights into fantasy are not necessarily diversions.

After Dinner Conversations

Have the kids study a character in depth, and prepare to join other

students

in a role play of an after dinner conversation. These need not be from

the same historical era. Wouldn't it be cool to see Einstein meet Tom

Paine,

Roseau, Mao, and Bakunin?

Plunk Your Magic Twanger, Froggie!

You may not remember the immortal Ghouldini of Parma, Ohio who

introduced

late-night monster movies on obscure tv channels. Your loss. The Ghoul,

a tasteless reprobate wearing a fright-wig and sun-glasses with only

one

glass, was plagued by a plastic frog that would leap out from behind

him

and mock him from time to time (plunking his magic twanger) during the

show. Froggie screaming, "Hi ya, Kids, Hi ya, Hi ya, Hi ya!" and

exposing

the Ghouldini as a fool. Invariably, at show's end, Froggie found

himself

being blown up by a cherry bomb in a toilet bowl-a sad end to a great

Frog.

This is not something you should do with children. (And,

actually the

Ghoul stole the bit from a 50's tv serial). But the vaudeville routine

can work well in classes. There are many vaudeville pieces that can be

sources of inspiration, like the Abbott and Costello bit, "Who's On

First?"

available in video stores everywhere.

Setting up a Ghoul-Froggie bit, say, with a politician giving

a speech

about family values, can be plenty of fun. Think of William Clinton

giving

spiritual guidance to the Surgeon General he fired. Well, of course do

not think about the substance of that interchange, but the form. It's

the form

that's the thing. Think of Froggie tormenting, say, Dan Quayle. You get

the drift, right? Who gets to be Froggie?

Circle of Responders

Everyone needs a response to writing and research. No one wants to be

kicked

about for doing it. So, set up a circle of responders, perhaps a group

of four, who share readings of each others' research work. One rule:

note

two good things for every criticism.

How Come That’s Funny?

You can start anywhere and go everywhere. For example, take a look at

an

old Harold Lloyd comedy. Is it still funny? How about an old Buster

Keaton,

a Charlie Chaplin, a Laurel and Hardy, an Abbott and Costello, then a

Martin

and Lewis? Then try a Beavis and Butthead, if you can get away with it,

or a South Park. How come this stuff is funny, if it is? Has humor

changed

over the years? How? Why? What is the social context of Chaplin’s

humor,

or Lloyd’s? Is there a relationship between economic conditions and

culture,

or what is the cultural milieu of South Park? For me, it doesn’t undo

fun

to unravel it. For some it is. You choose.

Every Trial is a Big Trial

It may be that the arena where citizens can use the widest range of

real

democratic rights (and conflict) in the US now is the court system. The

Southern Poverty Law Center has used the courts to bankrupt the Klan.

What

many people see as jury nullification in the O.J. Simpson trial caused

a national furor. The fact that two million people are now in US jails,

the highest per capita in the industrialized world, and the fact that

most

of those people are poor and had dubious representation, would seem to

indicate that questions of inequality penetrate the courts. Felons for

life are sometimes bicycle thieves, while Michael Milken, who bilked

retirees

of millions, served a few days and is now a stock advisor.

There is an infinite variety of trials to investigate,

possibly even

reenact-and plenty of film and paper archives too. You might want to

look

at the trial of the Wirtz, Commander of Andersonville, a southern

prison

camp, at the end of the Civil War. Or the Nuremberg trials which used

his

conviction as a basis for charging Nazi war criminals with crimes

against

humanity at the end of WW2. You could look at the Florida trials of the

El Salvadoran Generals, charged with abetting the torture and murder of

nuns in their country during a US funded anti-communist operation, in

November

2000, among the first so charged under an international law.

Investigate

the tragic trial of Joe Hill, an organizer for the Industrial Workers

of

the World, who was hanged after a trial in Utah in which the judge

refused

to allow him to fire his lawyer, who was pleading Joe guilty. Hill got

the death sentence, but not before he wrote to a pal, "Scatter my ashes

everywhere but Utah. I wouldn't want to be caught dead here." http://iww.org/.

Every trial is a big trial to those involved. Go look at the

local court

system in action. Be sure to see Small Claims Court, too. Or, if you

get

a ticket, take the kids. You could set up a system of redress for your

classroom too; but beware, kids can be harsh. The abused tend to abuse.

Marionette Plays

This works well in encouraging cooperative group work. It sweeps across

language arts, social studies, and encourages kids to see how stories

work,

in many ways. You can do this with shadow figures, using the light from

an overhead projector, or with puppets the kids make themselves. Kids

who

pay attention to detail, or learn to, can do a lot with this.

Follow the Money

Civics is often taught as if it took place in a fairyland, where

economics

never stands at odds with politics, where exploitation has nothing to

do

with democracy, or imperialism has no connection to missionaries and

the

Peace Corps. Investigating what is going on in fairyland, from the

school

board to the state legislature, is often a fruitful classroom activity.

Follow the money. get the contributions lists, the travel reports, the

Rolodexes and the daily calendars and the announcements for future

meetings.

Looking for cross-pollination of corporate positions, one fellow (sic)

will often sit on many-and the school board too. Make the natural

unnatural.

For example, remember that the reason there are bicameral legislatures

is because the propertied feared democracy, at the earliest days of the

US revolution.

Hey, What’s That Noise?

Taking away one of the senses is an interesting way to break, and

create,

enchantment. Take a tape recorder to a dairy farm, to a school, to a

Kmart,

to a social services office, a doctors’s office or hospital, a

restaurant

kitchen, a coffee shop, and make some tapes. Play them for the kids,

and

let them write a story about what they have heard.

History of Fairlyland

Nope, Snow White is not safe from critique. 'Jack Zipes has transformed

research on fairy tales from the superficial discussions of suitability

and violence to the linguistic roots and socialization function of the

tales. According to Zipes, fairy tales "serve a meaningful social

function

not just for compensation but for revelation: the worlds projected by

the

best of our fairy tales reveal the gaps between truth and falsehood in

our immediate society."After Zipes, no one can view a Disney rendition

with equanimity again.'

http://www.tc.umn.edu/~d-lena/Mythcon24%20Jack%20Zipes%20page.html.

Have kids rewrite the tales, as they have been written by

shifting social

relations over time.

Story Ladders and Story Boards

By the second or third grade (never underestimate them) many kids can

build

a story ladder or story board. The latter are simply drawings of the

key

sequences in a reading. In advertising, a story board is usually one

very

large board, broken into smaller squares. In each square, a key part of

the story is drawn, with related narrative or dialogue. Story ladders

can

be drawn, remarkably, like ladders, showing at each step, the title and

author, the key characters, the setting, the situation, the problem and

conflict, the resolution, and the reader's criticism.

Farmer Duck, the Story, the Book, the

Plan,

the Big Book

If you are unfamiliar with the kids’ book, Farmer Duck, go now to the

library

and read it. Then come back. Ready? So, you have read the Duck, what

some

call the Communist Manifesto for kids. Now, how might we expand on

that,

or any kids story, in a classroom? Well, to demonstrate the many

relationships

of stories, history, storytelling, and student agency; try this:

First, tell your kids the story of Farmer Duck, that hero of

all animaldom

who had nothing to lose but their Lazy Old Farmer. Let the story flow,

as it comes to you, from your memory of reading the book. Throw your

self,

your body, into it–and your voice and eyes and arms and legs. Then,

have

the kids discuss the story. What was this about anyway?

Now, take the book and read it to the kids, with all the

expressiveness

your denied stage-stardom can whomp up. Let the kids discuss this

reading,

noting that there are likely some differences with what you did in your

storytelling. Now, show the kids the stroke of genius you prepared late

last night, over that nasty cold cup of coffee: the print part of a big

book (for older kids, just give them the blank pages of the big book).

The print can be at the bottom of the pages of the big book, with

probably

2/3 of the page blank, but lined if you can get it.

Ask the kids if they would like to make their own book, and

illustrate

it. The print part is already done, but there is a lot of work still to

be done. There are illustrations for example, and choosing which way

things

will point, who will be represented, and how? If you can, get several

groups

of kids to work on different pages of the book. This will require that

they at some point gather as a planning group and prepare the entire

thing.

This will take some time, and struggle, but it makes a great

video tape

if you can detach enough time to do that as well.

Critique Tyranny

The celebrations of patriotism in most classrooms are witless.

Nevertheless,

most social studies educators gesture to the American Revolution as a

source

of inspiration. Unfortunately, under the lead of groups like the

National

Council for the Social Studies, the history of the bloody uprising

against

the King is muted by present-day calls to obey the law (part of the

MCSS’

“core democratic values” in Michigan) and to promote the national

interest.

Lost in all of that is the critique of tyranny that was the ideological

base motivating masses of people who risked their lives and homes to

kill

the British. (It is worthwhile to note that nearly the entire body of

African-American

leaders of NCSS quit the group in 1997, when, in a national meeting,

the

executive director of NCSS said, “This organization is not going to be

diverted by trivial questions about racism and sexism when we have

critical

business to conduct.”)

Aristotle, who believe that elites alone deserved the benefits

of democracy,

still addressed tyranny as a person,"responsible to no-one and

who

governs all alike with a view to his own advantage and not of his

subjects,

and therefore against their will. No free man can endure such a

government."

(From the Politics.) Aristotle’s early complaint, and its

contradictions,

still linger.

The critique of tyranny begins, at the same time, in two

places: criticism

of religious tyranny (absolute rule often girded by violence--

frequently

a velvet glove over an iron fist) and criticism of the denial of

property

rights. In revolutionary US society, the critique of property was aimed

at the monarchy–but spilled over into complaints about human rights as

well, like the right to not be kidnaped and forced into the monarch’s

navy.

On the one hand, people have consistently asked of their

world, “Isn’t

there more than this?” and responded to themselves that whatever more

there

might be must be in another world. Then an apostolic few offered to

interpret

just how to get to that other world, for a fee, and set up nearly

impassible

(often expensive) hurdles to make it. Along came critics, like Hegel,

who

analyzed in depth the alienation of people from nirvana, the ways

people

are set apart from not only the ways to understand and struggle toward

god, but from god him/herself. Hegel looked very carefully at the

processes

that history demonstrated, in his view, that moved people closer and

closet

to god, stripping the power of the priests. He was examining, not only

the reality of God, for him, but the ways history moves systematically

to bring people closer to God.

On the other hand, people have also objected, in revolutionary

ways,

to the material oppression that rises from inequality, rooted in unjust

property “rights,” (usually more precisely inheritance rights.) Marx

was

a scholar of religion who applied the religious critique of alienated

being

to the material world. He was able, then, to take Hegel’s analytical

scheme

called dialectics (the study of change) and apply it to the material

world.

This did more than turn Hegel upside down, it really was more like

turning

a balloon inside out. For Marx, then, was able to ask, “Why are we

separated,

alienated, estranged, from the central activity of our lives:work? Why

do people have less and less control over the processes of our labor,

nearly

no control over the products we make, and the more we do this, the more

we enrich the few people who profit from this great scam.” In brief,

Marx

was yelling, “Fraud!” at both the Pope and the Rockefellers. Bertell

Ollman

has a nice short explanation of this: http://www.richgibson.com/whatismarxism.html

The dual approaches to criticizing tyranny influenced the

great American

revolutionaries, from Thomas Paine to Tom Jefferson, and all in

between.

It was Jefferson, remember, who was calling for the Tree of Liberty to

be regularly cultivated with the blood of tyrants. To make the

revolution,

it was vital to motivate masses of peasant farmers with rhetoric about

equality and democracy, much of it heartfelt, even if it came from

slave-owners.

(When one considers property rights a key component of equality, one

can

rather easily believe that slaves, who are property, should have no

democratic

rights). However, when voting rights or democracy (not the same

thing)

have confronted property rights in the US, democracy usually lost. That

is the reason for bi-cameral legislatures, the electoral college, and

elaborate

voter registration procedures. The history of the Voting Rights Act (http://www.aclu.org/issues/racial/racevote.html)

is a history of this struggle. It is a telling fact that democratic

rights

do not exist, for the most part, at work.

An interplay of property rights and democracy is illustrated

by Henry

David Thoreau’s comment, “Political democracy is said to be the arena

on

which the battle of freedom is to be fought; but it surely cannot be

freedom

in a merely political sense that is meant. Even if we grant that the

American

has freed himself from the political tyrant, he is still the slave of

an

economic and moral tyrant.”

Now, how can all of this apply to a student in a US school in

the new

21st century? Rather than take this up as a distant historical memory

that

applies to no one but people with flintlocks, perhaps we can address

the

problem as a problem. and to bring all of the illuminating parts of the

social studies (history, geography, economics, political science,

psychology,

anthropology, sociology, etc.) to bear on it, each offering an new

insight.

For example, to see that there are answers in history that deal with

real

questions in school today, examine the relationship of the King to the

Colonist and the Principal and the Student Government. (For a fine

history

of the property/democracy struggle in the US, see Staughton Lynd’s Intellectual

Origins of American Radicalism, and Gordon Wood’s The

Radicalism

of the American Revolution.)

We can use the tools of psychology to answer the question:

“Why is it

that so many people do not notice injustice, and are willing to promote

it?” (Consider working class Nazis). Economics, the study of the

creation

and ownership of value (a key struggle of democracy, humanness and

property),

can assist in discovering not only where value comes from, but also why

it is that so few possess so much of it. Political science can address

the problem: “Why have government? Where does it come from? Is the

government

neutral, or a weapon of those who hold power/property?”

Double Dog Dare Ya

Unasked Classroom Questions

Here are some starter questions that few teachers are willing

to ask in serious ways.

- What is it to be free?

- Are we free? Are we free at work, at school, at play? If we

are not free: What would we need to know, and how would we need to know

it, in order to be free?

- Are there people among us who appear to be much more free

than others? If so, what is it that makes them

different? What do they have in common, worldwide?

- Who is less free? What elements do they have in common?

- Is freedom achieved through isolation, or friendly

connections with other people?

- If we are not free, in part because we are isolated from

each other, often in ways that we do not see (the

normalcy of segregated schooling), then what might we do to be more

free?

These questions rise from the Critique of Tyranny. This

critique has been applied to every society, ever since

the first food surpluses made inequality possible, and it became

possible to make an argument that separation

from others might be a good thing--in contrast to early societies where

those who behaved the most

collectively survived longest and best. The critique was the

interrogation of domination that, in ideas, forged

the US revolution. It is absent from most social studies textbooks.

The Critique of Tyranny leads to a question that can be asked

of any society, to judge it: How does this

society treat the majority of its citizens, invariably the workers, or

slaves, i.e., the common citizens, over time?

This reasonable question sweeps aside the notion that poisons

conservative forms of postmodernism, which

insist that there really is no rational way to judge any society, that

one society or social movement or idea might be as good as the next,

that all is mere viewpoint and, at the end of the day, maybe Mussolini

was not

such a bad guy after all.

Are teachers willing to ask these questions to students in

their classrooms, not of abstract distant societies, but

of their condition inside school? My experience is that most teachers

are not willing to seriously pose the issue,

in fear of lack of control.

Psychiatrist Robert Kaye says students in the world's

classrooms are not free, using a metaphor that suggests

that compulsory attendance laws make them "incarcerated." This would be

a good place to start. Are we here

because we want to be here?

Indeed, many teachers will insist that they live in a free

society. But they will also agree that they cannot probe

the question of freedom in school, or really speak their minds. The

Bill of Rights, for example, stops at the

door of most work places.

Here are some questions that students can work out themselves

to, perhaps, better understand the foundation

of most societies throughout history: The Master-Slave Metaphor.

In A Master-Slave Relationship:

- What does the Master want?

- What does the Slave want?

- What must the Master do?

- What must the Slaves do?

- How do Masters Rule?

- How do Slaves resist?

- What does the Master want the Slaves to know?

- What does the Slaves want the Master to know?

- What does the master want the slaves to believe?

- What does the slave want the master to believe?

- Is truth the same for the Master as it is for the Slaves?

- Who has the greater interest in the more profound truths?

- What mediates the relationship of the Master and the

Slaves-both in theory and practice?

- What elements within this relationship, as it exists,

provide clues to how the relationship might be changed?

- How will the slaves get from what is, to what they think

ought to be, without relying on magic?

- What will the Masters do in response to the struggles of

the slaves?

- Is it possible to end the relationship of Masters and

Slaves, or are people trapped within this forever?

- If people are not trapped in the Master-Slave relationship

permanently, and if they should actually overcome it,

what will preserve their common freedom?

References:

On Tyranny, by Leo Strauss

(the classic in the field)

History and Science for Boys

and Girls, by William Montgomery Brown (early success of friendly

connections, written in 1931)

Guns, Germs, and Steel, by

Jared Diamond

Phenomenology of the Spirit,

Hegel

Economic and Philosophical

Manuscripts, Marx (and all of the rest of Marx's work)

Alienation by Bertell

Ollman (why we are estranged from one another and how we might reason

our way out).

The Politics of Obedience, the

Discourse of Voluntary Servitude, Etienne De La Boetie

On Mussolini as a Kinder, Gentler,

Fascist, see the New York Times, 9/28/02 A17

Four-Squares

Form can impact how people feel about content. So can familiarity. The

British felt they had to call their new tank squads "cavalry."

Four-squares

is a game kids play in California. Here, it is something else.

Four-squares

are just a piece of paper folded so it has four sections, fold in half,

then fold again. Instead of asking the kids to write three paragraphs

on

whatever, ask them to make a book, a four-square, and in one section

write

their name and topic heading, what they did or analyzed on the second,

what they ascertained on the third, and how they savor that on the

fourth.

It's a diversion, artificial, but it seems to offset, "Do we gotta to

do

this?"

'Micro-Macro-Cosm

This is a tactic that creates a small group within the whole, a small

group

on display. Circle a relatively small group of students with the

remainder

of the class. Leave an open chair or two. The interior group is tasked

to engage a discussion about a given topic, while observers can move in

and out of the smaller group by briefly occupying the vacant chair(s).

Another way to do this is to have the class, in small groups, raise

questions

and take positions about a controversial issue, and then send delegates

into the interior group for a discussion.

The most powerful weapon in the hands

of the

oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.

Steve Biko, the South African activist who was murdered by the

apartheid

regime while he was in custody, said that. The next paragraph is from

David

Barsamian, a historian.

He’s quite accurate. Most oppression succeeds because its

legitimacy

is internalized. That’s true of the most extreme cases. Take, say,

slavery.

It wasn’t easy to revolt if you were a slave, by any means. But if you

look over the history of slavery, it was in some sense just recognized

as just

the way things are. Well do the best we can under this regime. Another

example, also contemporary (its estimated that there are some 26

million

slaves in the world), is women’s rights. There the oppression is

extensively

internalized and accepted as legitimate and proper. Its still true

today,

but its been true throughout history. That’s true in case after case.

Take

working people. At one time in the U.S. in the mid-nineteenth century,

a hundred a fifty years ago, working for wage labor was considered not

very different from chattel slavery. That was not an unusual position.

That was the slogan of the Republican Party, the banner under which

Northern

workers went to fight in the Civil War. Were against chattel slavery

and

wage slavery. Free people do not rent themselves to others. Maybe

you’re

forced to do it temporarily, but that’s only on the way to becoming a

free

person, a free man, to put it in the rhetoric of the day. You become a

free man when you’re not compelled to take orders from others. That’s

an

Enlightenment ideal. Incidentally, this was not coming from European

radicalism.

There were workers in Lowell, Mass., a couple of miles from where we

are.

You could even read editorials in the New York Times saying this around

that time. It took a long time to drive into people's heads the idea

that

it is legitimate to rent yourself. Now thats unfortunately pretty much

accepted. So that’s internalizing oppression. Anyone who thinks its

legitimate

to be a wage laborer is internalizing oppression in a way which

would

have seemed intolerable to people in the mills, lets say, a hundred and

fifty years ago. So that’s again internalizing oppression, and its an

achievement.

What might that have to do with teaching, the struggle over

what people

know and how they come to know it?

Rewriting Textbooks

If you lack the power to throw out the textbook, rewrite it with the

kids.

Let assigned groups of kids review particular sections of the text,

review

what is said, and how it is said, and apply good question to what is

going

on (see questions for criticism on my www page). Then let the groups

report

out, and rewrite the book. http://www.richgibson.com/QUESTCRI.html.

Culture Jammin’

An appreciative “Thanks,” to Bill Boyer for this one, in sincere hope

that

he gets tenure. Culture jammin’ inverts, turns inside-out,

cultural

artifacts like Joe Camel ads, or Coke ads, or your choice from the

deluge

that is poured upon children in school. For example, take any kids

magazine

and give students the opportunity to hold it up to ridicule by creating

their own counter-advertisements which they may be able to post around

the school–even for a moment. One group of students focused on how Joe

Camel might look with skin cancer, and did some art work to accompany

their

effort. The called him “Joe Chemo.”Another group did some poster- ads

for

the cafeteria food, which you can imagine. Yet another examined the

relationship

of Coke (which had a contract with their school) and tooth decay, and

did

some graphic counter-advertising about that. The possibilities for

extensions

are limitless.

Informational Picketing

This is less risky than it sounds, but it is wise to know your

community.

Informational picketing can be in favor or something, or against it.

"Clean

the wetlands,"or, "Don't die, don't smoke," etc. Show the kids how to

make

a placard or picket sign, assuming the background research is done,

etc.

Sham Interviews

Kids seem to love this, especially the precocious pre-Barbara Walters

set.

Kids then need to do background research on their characters, and to

create

great questions to make the interview go forward. See also, the CBS

Edward

R. Murrow series, "You Are There." This was one of the most popular TV

news programs in history. Murrow's commentary eventually was key to the

ruin of fascist Senator Joe McCarthy. Take a look at his work as a

guide

superior to Walters'.

Reification is Forgetting

Reification is turning a human construction into an uncriticized icon,

allowing what seems to be normal to limit investigation–and then

allowing

that normalcy to become oppressive. A high-point of reification

might

be a plastic Jesus, a human construction which not only locates a

better

world in death, but offers strict rules of normalcy in life. But here

are

two better examples:

As I write here in San Diego, California is in the midst of a

series

of power blackouts that have stretched across the state for two weeks.

Predictions are that the outages will continue for a year–in the

richest

state of the richest country in the history of the world. Mainstream

press

reports limit the exploration of this crisis. On the one hand, they

fail

to investigate where it is energy-power comes from (the

combination

of all the inter-related process of the natural world; water power for

example) and on the other hand, they ignore the interconnection of

natural

forces with labor and technology (the Hoover damn and publicly

funded

research) going back hundreds of years. Normalcy, then,

eliminates

the idea that electricity is the product of natural forces that it

makes

no more sense to privately own than air, and eliminates the history of

labor and struggle that rationally cannot be possessed by a few. It is

“normal” that electricity should be owned. Normalcy forgets. A

teacher’s

task is to assist others in remembering, and to create the wonder that

goes along with knowing that somebody wants things forgotten–or gains

from

forgetting. There are plenty of history texts that explain the

background

of the crisis, beginning with Carey McWilliam’s classics. They don’t

turn

up in the San Diego Times Union.

Consider the grocery store in an urban area. How come it looks

like

that–a huge parking lot with a building set far back from the street

and

sidewalks–hundreds of square yards of space that could be profitable

simply

lost to auto storage? The answer is in history, a history I thank my

friend

Paul for helping me to re-see.

Grocery stores are, like all businesses, there to make a

profit. The

struggle over their profits has been intense. Consumers want lower

costs

and sometimes shop competitively. Suppliers want their piece. The

work-force

in a grocery store has some advantages in controlling their work place:

the employer cannot completely leave, go to the third world, although

the

employer can go to the suburbs. The routes into and out of the grocery

store can be somewhat controlled by workers if, for example, unity can

be built between the Teamsters who deliver goods, and the Food Workers

who work in the store. This explains why, in California and Michigan

for

example, grocery workers remain unionized in an era of union collapse,

and why, where the unions have resisted, they are fairly well-paid.

But why the geography of the modern grocery store with that

huge parking

lot? Well, of course there is our society’s reification of the

automobile,

which became the normal mode of transportation in only the last fifty

years.

But there is a deeper reason. The parking lot does not have to be where

it is. It could be behind the store, with the storefront on the street.

But it could not be there if the employer wanted to be sure to be able

to control entrances and egresses, on the chance of employee picketing,

informational or otherwise. The reason for the geography of the grocery

store is an intersecting history of the struggle of workers, bosses,

and

modern transportation, a history that needs to be noticed, and

remembered.

Now, why does your school look like that?

We Gotta Get Outa This Place

There is no particular reason to be trapped in a school. Teachers have

bargained all kinds of long-term moves elsewhere. For example, you

might

be able to turn a problem of school overcrowding into a good thing:

suggest

that your classroom be moved to a local museum for the year. Spending a

year wandering around a museum with some reasonable guidance ratchets

up

kids vocabulary, world view, sense of history, and their literary

skills.

You could also move to a library, using their community rooms, or to a

gym. A year out of ‘school’ can create a better kind of schooling. See

the records of the Schools in The Park program in San Diego.

Storytelling

This is an art. The way to people's minds is through stories. Much of

Christian

organizing is based on this thesis. Storytelling should involve the

soul

and the head, as does everything, but more obviously so. Have the kids

story board (chart out) a story they choose, or one they make up.

Invite

a storyteller to class as a model (they are all over the place). Work

on

volume, eye contact, etc. Show' em the pictures! http://falcon.jmu.edu/~ramseyil/drama.htm.

Mock Legislative Hearings

Legislative hearings can demonstrate all the powers of interest groups,

not just a debate between senators, and should reflect not only the

power

of debate, but of the conflicting relationship between those who have

the

people and those who have the money. While mock is meant here to mean

"play,"

parodies are always good. They require both a sound understanding of

the

point to be made, and humor. People will not laugh hard, though, unless

they agree with the politics.

Duration Lines

Start with the kids lives. Let them construct the time lines of their

lives,

and make a length-chart of them. That means not only selecting

important

events, but deciding how much space those events will be allocated. Go

home and discover ten things that happened to you since you were

born-and

when they happened. Then work with them to chart those events.

Fly Me to the Moon

Most nine-year-olds probably know more about astronomy than I do. Even

so, there is no better way to show how the basics of geography work

than

by setting up the entire universe in your classroom. You can do the

beginnings

with just a few kids–and a little space after you clear away some

desks.

Have one child be the sun, full of pulsating energy (do not pick the

child

who is already full of pulsating energy). Another kid is the earth,

spinning

and rotating around the sun. Another kid is the moon....and before you

know it–space travel, longitude and latitude, and the transformation of

the dinosaurs. Use you imagination.

Surveying for Surveillance

This is like counter-spy vs spy. Children are under constant

surveillance,

more so in the US in the 21st century than ever before. The

cameras, organized supervised games, metal detectors,

stop-and-freeze-when-I-blow-the-whistle

routines, daily reports, etc., are now part of normalcy. So, part of

the

job of social studies is to expose and unravel what is normal, and then

wonder if it is. Have the kids take a look at who is watching them,

when,

how, and why. Wonder, do we really need to be so noticed, seen, heard,

recorded? A geographical map of child surveillance can prove

interesting.

You peek at me. I peek at you. Surprise. Peek-a-boo.

"I

ain't the worlds

best writer nor the worlds best speller,

But when I believe in

something I'm

the loudest yeller."

--Woody Guthrie (1950)

Blues shouting, chants-and-response, gospel choirs, Good Golly Miss

Molly,

folk singing, John Coltrane; all are signals of the unity of the mind

and

body, of sound and silence, of the affective and cognitive. And all

have

substance in political economy (what is the reason we now have

color-coded

radio stations and rating charts?), in the study of domination and the

arts of resistance ("Follow the Drinking Gourd"), and the tenor of the

times. No study of the twenties without jazz, no study of the sixties

without

the outrage of Little Richard, and one goes right to the other.

Consider the politics of, "This Land is Your Land, this Land

is My Land,"

by Woodie Guthrie and ask if that is better than the current national

anthem

(there was a congressional debate about it). Songs have always been

concerned

with history and society, and reflected/recreated what they portray.

Take

for example the song, "Bread and Roses," http://www.breadandroses.com/real.audio.1.html.

This brilliant, moving, powerful song came out of the strike of women

textile

workers in Lawrence Mass, the first major strike in US history that was

won. An investigation of the Bread and Roses strike, which leads to

song

writing, play writing, little newspapers, etc., could be a momentous

class

event. Here is a song:

Solidarity Forever

Written by Ralph Chaplin, Jan. 1915

Tune: "John Brown's Body"

When the Union's inspiration through the workers'

blood shall

run,

There can be no power greater any-where beneath the sun;

But what force on earth is weaker than the feeble strength of

one?

But the Union makes us strong!

Chorus:

Sol-i-dar-i-ty for-e-ver,

Sol-i-dar-i-ty for-e-ver

For the Union makes us strong.

Verse 2: